Well I never!

By Richard Peters

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, where one could venture beyond the self-isolationist quarantine of one’s own four walls without fear of contamination, a colleague of mine visited a local brewery here in Munich, where she was greeted by the sight of a beer mat on which were inscribed the immortal words:

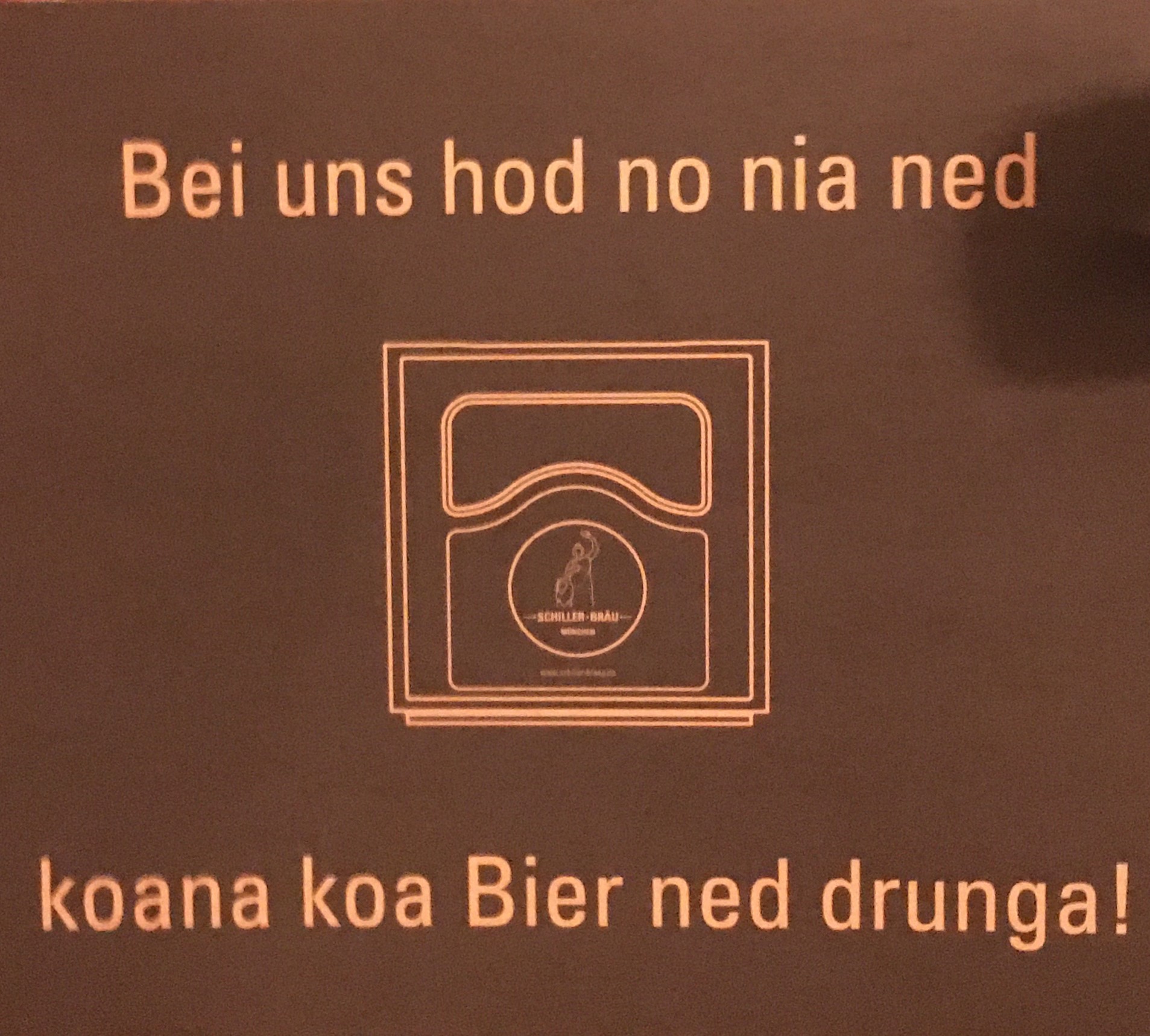

Bei uns hod no nia ned koana koa Bier ned drunga!

This piqued not only her thirst but also her linguistic interest. After picking her way through the heavily accented Bavarian dialect to distill the meaning of this phrase, she realised that the message itself was somewhat banal – clichéd, even, in a brewery setting: “No-one has ever not drunk beer here!”

But to cut to the informational chase in this way is, of course, to shatter the charm of the slogan, which consists precisely in its baroque, convoluted evocation of olde-worlde, simpler times – ur-Bavarian times, if you will, when laughing with friends and drinking beer were all that mattered.

My colleague quickly pushed these melancholy thoughts aside – no doubt with the aid of a goodly helping of said fermented beverage – to ruminate on what exactly was going on with this statement. HOW many negatives? And yet still it manages to somehow warm the heart? Artfully articulated tidings indeed!

There are fully five negative forms in play here: “no nia” (never yet); “ned” (not), “koana” (nobody), “koa” (no), and another “ned” (not) for good measure. How is it that the human mind can fight through all this negativity and grasp the intended idea – that beer is good and popular – without dismay? Perhaps this is a uniquely Bavarian talent?

The English language abhors multiple negatives. Or so we’ve been led to believe ever since Robert Lowth, an 18th-century English bishop and scholar, wrote in his 1762 A Short Introduction to English Grammar:

“Two negatives in English destroy one another, or equivalent to an affirmative.”

Unfortunately, Lowth’s dedication to grammar was matched only by his love of criticising other people’s usage – even that of renowned authors and playwrights – based on nothing but his own preference. As the Johnson column in an issue of The Economist earlier this year puts it, “Lowth is considered responsible for some of the hoariest non-rules of the English language – proscriptions that were invalid even when he wrote them, but which have nonetheless been imposed on schoolchildren since.”

Writers of modern English are now stuck with shibboleths like “never end a sentence with a preposition” (another of Lowth’s gems) and an almost moral expectation that we will avoid using more than one negative element to express negation – even though such usage is absolutely natural in spoken English as it is in the speech and writing of many other languages. I don’t never need no Bavarian blood in me to not drink no beer without none of them negatives no more!

It’s a fair bet that, were we miraculously to transport our 18th-century friend to modern-day central Europe, he would turn his principled grammarian’s nose up at the inspired Bavarian advertising claim that so tickled my colleague’s fancy. Luckily, that is a truly fantastical prospect; sadly, so is any thought – at present – of visiting the brewery myself to investigate.

Of course, like matter and antimatter, the double negative, which equals a positive, has a theoretical opposite, the double positive, which ought to equal a negative, but cannot exist in nature. In this, language is no different from maths: everyone who paid attention at school will know that if you multiply two negative numbers together you always end up with a positive result. And so it is with language, isn’t it? There’s simply no such thing as a double positive! Yeah, right.