How I learned to compose myself and paint you a picture

By Colin Rae

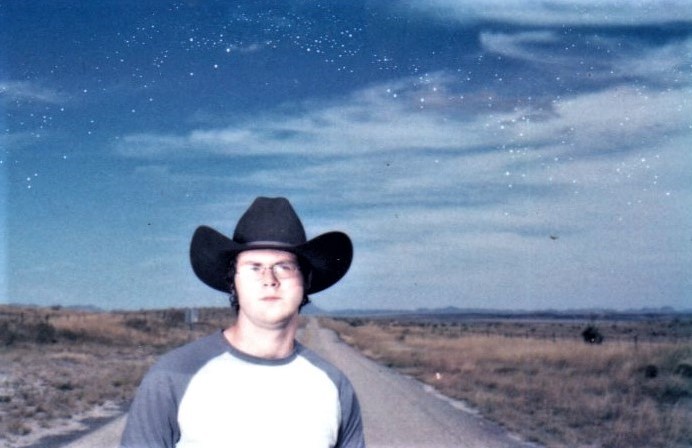

Twenty-one years ago, almost exactly half my life ago, I took a trip that changed everything for me. I had just completed my third year at Edinburgh College of Art and had arranged to spend the summer as an intern at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas. Not only would my time there alter the focus of my practice, both as a visual artist and a writer, but it would also open the door to a new life – and in Germany of all places.

Trepidation. Fear. Excitement. Bewilderment. These were the emotions surging through my body as I careened through the winding streets of Edinburgh in the back of a taxi headed for the airport. As I was bounced up and down by sharp turns on shiny cobbled streets, the enormity of what I had done began to sink in. I had only just turned 21 and I was off to spend the next three months in a tiny town in the far west of Texas. Why was I prepared to travel over 3,500 miles to spend the summer in a town of roughly 2,000 inhabitants in the middle of the desert? Art, that’s why.

In art, as in translation, context is king

For a full account of the events of that summer, dear reader, you’ll have to wait for me to publish my memoirs. Nor do I have space here to provide a worthy explanation of what the Chinati Foundation is and does. So here’s the ultrashort version: Chinati was established in 1986 by artist Donald Judd (1928–1994), who took more care and control over how his work was installed and exhibited than perhaps any other artist. Chinati is a public museum “in which artists have determined how their work will be seen in permanent relationship to architecture and the land.” As an intern, my responsibilities included giving tours of the collection, so I had plenty of opportunities to see for myself that the museum succeeds in minimising the interference between the work and the viewer.

Chinati is located on a former US military based on the edge of a small town in the desert: a place that’s near a place that’s not near anywhere at all really. The upshot of this remote location is visitors to the collection are already far removed from their everyday lives and distractions. As there’s very little there, there’s very little to get in the way. The viewer can simply focus on the artwork in this deliberately uncluttered context.

As you may have read about in some of our other blog posts, one of the tightropes we have to walk as translators, editors, and copywriters is the one between content and contrition: include too much information and the point might get lost; skimp on the details and risk frustrating or confusing the reader. When I’m translating, I’m always looking for the most efficient way to include all the information from the source text without adding anything that’s going to inhibit getting the author’s message across. In other words: content, context, clarity.

The first of my “Applause” series of artworks from 2010

This is what Chinati does exceptionally well with its permanent installations. Dan Flavin’s untitled (Marfa project) is probably my favourite installation in the collection. Completed in 1996 and spread over six buildings, this interaction with different combinations and placements of fluorescent light is made all the more powerful by its setting. Each building is U-shaped, with the installations occupying the closed end. You enter each space through a door at one of the open ends and your senses are immediately heightened by the sudden cool after the Texas heat outside. There’s also virtually no noise, save the gentle warm hum coming from the far end of the corridor. The only natural light comes from two modest windows at the entrance ends of each wing. The walls are empty, smooth, and white (I remember some visitors asking what was going to be hung on the walls, not grasping that the whole space was part of the work). In some of the buildings, the light tubes are visible as soon as you enter, in others you have to walk up to the closed end before you see them. As is typical at the museum, there are no signs or stickers giving details of the artist’s name, life story, or intentions. And as tour guides, we were encouraged to say as little as possible and leave visitors to engage with the work.

I’ve visited scores of other museums and galleries all over the world and very few pull this off. Most are too cluttered and crowded for visitors to achieve anywhere near the kind of emotional interaction and intimacy with the art on display that they can at Chinati. Some even seem to go out of their way to irritate and distract their patrons. I’ve seen minimalist sculptures hung on walls peppered with random holes and scuffs, delicate Impressionist paintings hung upsettingly close to dehumidifiers, and don’t even get me started on the various conventions for displaying titles and other information. Bad installation drives me crazy – especially as it is 100 percent avoidable.

Rogues’ gallery

I follow a fun Instagram account called greatartinuglyrooms, which – as the name suggests – is all about artworks (mainly reproductions) that have been installed in extremely unsuitable and unflattering places. A friend and former tutor of mine from art collage has done a significant amount of research into how art is installed and has collected a great many photographs of “interesting” installation choices. He calls this work “Monkey Business”, a name fittingly inspired by something Judd wrote in his Statement for the Chinati Foundation: “Somewhere a portion of contemporary art has to exist as an example of what the art and its context were meant to be. […] Otherwise art is only show and monkey business.”

“Untitled (Angel)”, Colin Rae, acrylic on board, 2010

My time in Marfa introduced me to a wider world and gave me the appetite and confidence to discover it: while I was there, I met a Munich-based photographer who invited me to spend some time assisting him around the US and in Germany. I felt very comfortable in Munich and – to cut another very long story short – I settled here in 2003.

Given my newfound zeal for curating context and minimising the interference between sender and recipient, moving to another country might seem like an odd thing to do. Living life in another language added a new level of interference, sometimes making even the simplest things cumbersome and complicated. But moving here also wiped the slate clean and allowed me to create a new context for myself and my work. The struggles I faced learning the intricacies my new home’s language and customs only strengthened my resolve to break down barriers. I’m always going to be from somewhere else, but I’ve found the right space in which to curate my life. Every artwork I’ve made and everything I’ve written since leaving Marfa has been an attempt to give an idea its best expression within its intended context.